The poison dart frog, known for its dazzling colors and potent toxins, is one of the most fascinating amphibians on Earth.

Native to Central and South American rainforests, these small yet vibrant creatures have evolved an extraordinary defense mechanism through their toxic skin secretions.

Despite their tiny size, their poisons can deter or even kill predators. This complete species guide explores their diverse habitats, unique adaptations, diet, reproduction, and conservation status.

By understanding their ecological importance and the threats they face, we can appreciate how these remarkable frogs contribute to the balance and beauty of tropical ecosystems.

What Are They?

Poison dart frogs (also sometimes called dart-poison frogs or simply “poison frogs”) encompass a group of species in the family Dendrobatidae.

They are typically diurnal (active during the day) and many exhibit bright body colours, this combination of traits is linked to their chemical defences.

Only a handful of species (from the genus Phyllobates) have been documented as being used by indigenous peoples to tip blow-darts with their toxins; despite the common name, not all poison dart frogs are lethal to humans.

Characteristics & Appearance

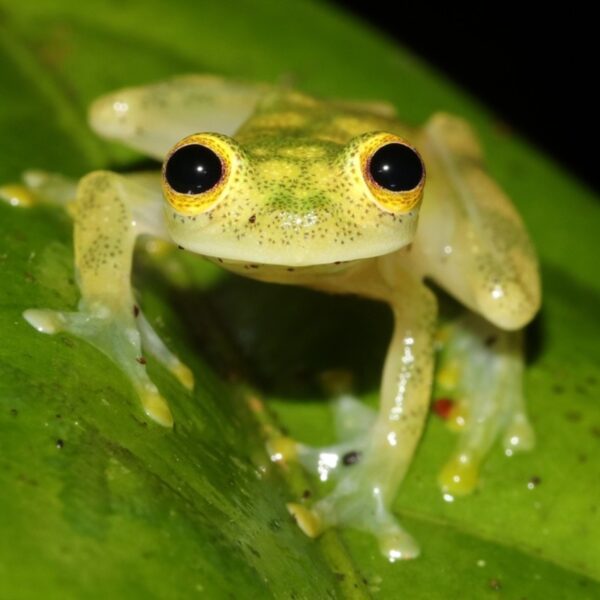

Most poison dart frogs are small, some less than 1.5 cm in adult length, though a few grow up to around 6 cm. They weigh on average about 28 g.

Bright coloration is a hallmark for many species: these vivid patterns serve as a warning to predators (a strategy known as aposematism). ,

In contrast, some species that consume a more generalist diet display cryptic (camouflaged) coloration and little to no observed toxicity.

Habitat & Distribution

Poison dart frogs are native to humid, tropical environments of Central and South America, including countries such as Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela.

They dwell primarily in tropical rainforests, but can also be found in higher altitude shrubland, marshes, and even degraded forest habitats depending on the species. They tend to live on or near the ground, but some even climb trees up to 10 m high.

Taxonomy & Diversity

The family Dendrobatidae contains around 16 genera and roughly 200 species. Some of the genera include Adelphobates, Andinobates, Ameerega, Dendrobates, Oophaga, Phyllobates, Ranitomeya, among others. Within these genera, many species show remarkable variation in colour and pattern, so much so that what was once considered a single species may contain multiple colour morphs.

For example, Dendrobates tinctorius, Oophaga pumilio and Oophaga granulifera are known for colour-pattern variation.

Toxicity & Chemical Defence

One of the most fascinating aspects of poison dart frogs is their chemical defences. They secrete alkaloid toxins from skin glands.

Some of the known toxins include allopumiliotoxin 267A, batrachotoxin, epibatidine, histrionicotoxin and pumiliotoxin 251D.

These toxins are not synthesized de novo by the frogs; rather, they are sequestered (accumulated) from their diet, primarily ants, mites and other arthropods that contain the alkaloids. This is known as the diet-toxicity hypothesis.

Interestingly, frogs raised in captivity on diets lacking the necessary arthropods do not develop the same level of toxicity. The most toxic species is the golden poison frog (Phyllobates terribilis). On average, each individual carries enough toxin to kill dozens of humans or many thousands of mice.

In addition to their defensive role, these toxins are of scientific interest: for instance, epibatidine (from some species) is a compound around 200 times as potent as morphine as a pain-killer, although its therapeutic window is dangerously narrow.

Behaviour, Reproduction & Life Cycle

Territoriality and aggression: Both male and female dart frogs can be territorial, defending areas used for calling (in males) or nesting sites. Physical contests, vocal displays and wrestling are part of their behavioural repertoire.

Reproduction: Many species of these frogs are dedicated parents. For example, in some genera (such as Oophaga and Ranitomeya) the parent will transport newly hatched tadpoles on their back to small pools of water (such as those that accumulate in bromeliads) high up in trees. There the tadpoles continue development and in some cases the mother deposits unfertilised eggs as food.

Courtship is interesting: males typically call from morning onward, often perched on stems or logs, to attract females. The female usually initiates tactile courtship, while the male may select the oviposition (egg-laying) site and lead the female there.

Tadpole behaviour: Some species’ tadpoles exhibit predatory and even cannibalistic behaviour, consuming other tadpoles or mosquito larvae in resource-poor environments.

Captive Care & Life Span

In captivity, while the vivid colours and small size make dart frogs popular among amphibian hobbyists, there are important care considerations. Wild-caught specimens may retain toxicity for some time due to accumulated alkaloids, so handling requires caution.

Under proper conditions (high humidity ~80–100 %, daytime temperatures ~22–27 °C, nighttime no lower than ~16–18 °C), many species thrive. Some have reported lifespans up to 25 years in captivity.

Conservation Status & Threats

Many poison dart frog species face significant conservation challenges. Threats include habitat loss (from deforestation, agricultural expansion), the pet trade, and diseases, especially the chytrid fungus Chytridiomycosis (caused by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) which has decimated amphibian populations worldwide.

Because of their often restricted ranges and specialised habitats, some species are listed as threatened or endangered. Captive breeding programs, habitat protection, and disease mitigation (for example antifungal treatment in captive frogs) are among the conservation measures in place.

Why They Matter & Fascinating Facts

The brightly coloured patterns of dart frogs are an elegant natural example of aposematism, warning colours signalling toxicity to predators.

Their chemical defences derive from diet and represent a compelling link between ecology, evolution and chemistry.

Some of their toxins have potential medicinal uses: for example epibatidine led to painkiller research (though human use proved dangerous).

Their intricate parental behaviours, such as carrying tadpoles to tree-holes or bromeliads and feeding them unfertilised eggs, show remarkable evolutionary adaptation to rainforest micro-habitats.

Although the term “dart frog” gives the impression that all are deadly, in fact only a few species (notably Phyllobates) are lethal to humans; many others are harmless or only mildly toxic.

Summary

In sum, poison dart frogs are a striking group of Neotropical amphibians whose vivid colours, unique behaviours, and chemical arsenals make them one of nature’s most intriguing examples of how diet, ecology, evolution and warning displays come together.

From the leaf-litter floor of a rainforest to the tiny bromeliad pool high in the canopy, these frogs live lives full of strategy, whether it’s securing territory, transporting tadpoles, or deterring predators with potent alkaloids. Yet for all their brilliance, many species face urgent threats, reminding us that the wonder of these frogs is tied closely to the health of their rainforest homes.