If you’ve ever heard a deep, resonant “jug-o-rum” echoing from a pond on a warm summer night, chances are you’ve encountered the American bullfrog.

This impressive amphibian isn’t just another frog—it’s the heavyweight champion of North American frogs, and it has some seriously fascinating traits that make it stand out from the crowd.

Meet the American Bullfrog

The American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) is native to eastern North America and is hands-down the largest true frog on the continent.

We’re talking about a frog that can grow up to 8 inches from snout to vent and weigh as much as 1.8 pounds—that’s roughly the size of a small dinner plate. Most adults you’ll encounter measure between 3.6 to 6 inches and weigh anywhere from 5 to 175 grams during their first eight months of life, but the real giants can tip the scales at 500 grams or more.

What really sets bullfrogs apart is their distinctive call. Males produce that famous bull-like bellow during breeding season—hence the name “bullfrog”—and it’s a sound you won’t soon forget.

This vocalization serves as both a territorial warning to other males and an advertisement to potential mates, carrying across water bodies for impressive distances.

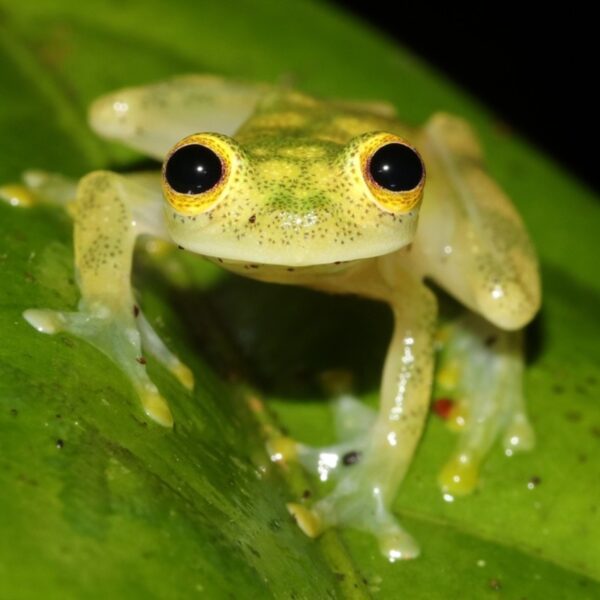

A Closer Look at Their Appearance

Bullfrogs are genuinely striking creatures when you take the time to observe them up close. The upper surface of their body displays an olive-green base color that can be either solid or decorated with mottled grayish-brown patterns—perfect camouflage for their aquatic lifestyle. Flip one over (gently, of course) and you’ll see an off-white belly blotched with yellow or gray markings.

One of the most noticeable features is the stark contrast between their bright green upper lip and pale lower lip.

Their eyes are prominent and beautiful, with brown irises and distinctive horizontal, almond-shaped pupils that give them excellent vision for hunting.

Just behind those eyes, you’ll spot the tympana—the eardrums—which are actually visible on the surface and surrounded by distinctive folds of skin called dorsolateral ridges.

Here’s a cool detail about sexual dimorphism in bullfrogs: males and females look noticeably different. Males are actually smaller than females but sport bright yellow throats that they flash during territorial displays. The real giveaway is the tympana size—in males, these eardrums are significantly larger than their eyes, while in females, they’re about the same size as the eyes.

Males also develop more muscular forelimbs, which comes in handy during the lengthy amplexus (mating grasp) period.

Their limbs tell another story about their lifestyle. The front legs are short and sturdy—built for stability rather than distance. The hind legs, though, are powerful and long, designed for those explosive leaps bullfrogs are famous for.

While the front toes have no webbing, the back feet feature extensive webbing between most digits (except the fourth toe), making them incredibly efficient swimmers.

Where Do American Bullfrogs Live?

Originally, American bullfrogs called eastern North America home. Their native range stretches from the eastern Canadian Maritime Provinces all the way down to the Gulf Coast, and from the Atlantic seaboard west to the Mississippi River and beyond into states like Idaho, Texas, Michigan, Minnesota, and Montana. Interestingly, they’re largely absent from North Dakota, but they’ve made themselves comfortable in nearly every other eastern U.S. state.

These frogs are habitat specialists with specific requirements. You’ll find them in large, permanent water bodies—think swamps, ponds, and lakes that don’t dry up seasonally.

They’ve also adapted remarkably well to human-altered landscapes, colonizing koi ponds, canals, ditches, culverts, and even swimming pools. The key requirement is permanent water with plenty of vegetation along the shoreline.

But here’s where things get complicated: bullfrogs have become one of the world’s most widespread invasive species.

They’ve been introduced to the Western United States, South America, Western Europe, China, Japan, South Korea, Southeast Asia, Mexico, Belgium, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Italy, Jamaica, the Netherlands, Puerto Rico, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Why?

Mostly for food production—bullfrog legs are considered a delicacy in many cultures—but also for biological pest control and even as released pets.

The Invasive Species Problem

The bullfrog’s success as an invasive species is both impressive and concerning. These frogs possess a voracious appetite and can produce up to 20,000 eggs in a single breeding event, giving them a massive reproductive advantage. In places like California, they’ve become a serious threat to the endangered California red-legged frog, and they’ve been implicated in the decline of numerous native amphibian populations worldwide.

What makes bullfrogs particularly problematic is their apparent resistance to chytridiomycosis—a devastating fungal disease that’s been decimating frog populations globally. Scientists worry that bullfrogs may act as asymptomatic carriers, spreading this lethal fungus to more susceptible native species as they invade new territories. It’s a perfect storm of invasiveness: they’re tough, adaptable, disease-resistant, and incredibly successful breeders.

Some regions are fighting back, though. In 2023, the Utah Department of Natural Resources even started tweeting cooking tips to encourage residents to catch and eat invasive bullfrogs, turning a conservation problem into a culinary opportunity.

What Do Bullfrogs Eat?

Calling bullfrogs “voracious” might be an understatement. These are opportunistic ambush predators with an “if it moves and fits in my mouth, I’ll eat it” mentality. Stomach content analyses have revealed an astonishing variety of prey including rodents, small lizards, snakes, other frogs and toads, crayfish, small birds, scorpions, tarantulas, and even bats.

What makes the bullfrog’s diet unique among North American ranid frogs is the high percentage of aquatic prey. They regularly consume fish, tadpoles (including their own species), ram’s horn snails, dytiscid beetles, and the aquatic eggs of fish, frogs, insects, and salamanders. Cannibalism is documented in bullfrog populations, especially when resources become limited.

The mechanics of their feeding strategy are fascinating. They’re sit-and-wait predators that remain motionless until prey comes within striking distance. When prey movement triggers their hunting response, the frog first rotates its body to face the target, then makes approaching leaps if necessary. The actual strike is ballistic and lightning-fast—the frog lunges with eyes closed, mouth opening, and that sticky, mucus-coated tongue shooting out to engulf the prey.

Here’s where it gets really interesting: the speed of a bullfrog’s tongue strike is faster than muscle contraction alone could achieve. Similar to a slingshot mechanism, elastic tissues in the tongue and tendons in the lower jaw store tension when the mouth is closed. When the frog strikes, this stored elastic energy releases explosively, completing the entire strike and retrieval in approximately 0.07 seconds—faster than most prey can react. Even better, this elastic-force mechanism works independently of body temperature, so a cold frog can strike just as fast as a warm one.

For larger prey that doesn’t fit entirely in the mouth, bullfrogs use their hands to stuff it in. Laboratory observations show bullfrogs taking mice often swim underwater with their prey, effectively drowning warm-blooded victims through asphyxiation. They can even compensate for light refraction at the water-air interface, striking at a position slightly behind where prey appears to be located.

Breeding Season Drama

The bullfrog breeding season is an intense affair lasting two to three months, typically running from late May through July in northern populations. Males arrive at breeding sites first and stake out territories, spacing themselves about 10 to 20 feet apart. Once established, they begin their loud advertisement calls to attract females and warn off rival males.

Male bullfrogs actually produce at least three different types of calls depending on the situation. There are territorial calls directed as threats toward other males, advertisement calls to attract females, and encounter calls that precede physical combat. This vocal repertoire plays a crucial role in the complex social dynamics of bullfrog breeding aggregations.

These breeding aggregations are called choruses, and they function similarly to bird leks—communal display areas where males compete for female attention. What’s fascinating is that these choruses are highly dynamic, forming and breaking apart over just a few days, then reforming in different areas with different groups of males. Males are remarkably mobile within and between choruses, constantly seeking optimal breeding positions.

The sex ratio at breeding sites is heavily skewed toward males, which creates intense male-to-male competition. Older, more experienced males tend to secure the prime, centrally-located territories within choruses, while younger males get relegated to less desirable peripheral spots. Females, in contrast, have brief periods of sexual receptivity—often just a single night—and they’re highly selective about which males they’ll accept.

Here’s something that overturns old assumptions about frog mating: females actually initiate physical contact, and males only clasp females after they’ve indicated willingness to mate. This refutes earlier claims that male frogs will indiscriminately grab any nearby female. Female choice appears to be a sophisticated process influenced by male position within the chorus, call quality, territory quality, and various male display behaviors.

Social dominance within choruses is established through impressive visual displays and physical contests. Territorial males float high in the water with inflated lungs, displaying their bright yellow throats. Non-territorial or subordinate males adopt a low posture with only their heads above water. When two dominant males encounter each other, they engage in wrestling bouts, clasping each other in an upright position that lifts both well above the water surface.

Some males adopt what researchers call the “silent male” or “satellite male” strategy. These individuals remain submissive, position themselves near territorial males, make no calls, and don’t attempt to intercept females. They’re essentially waiting for territories to become vacant—a lower-risk, lower-reward reproductive strategy.

Maintaining chorus tenure (the number of nights a male participates in breeding activity) is costly. Males face increased predation risk, lost foraging opportunities, and substantial energy expenditure from calling and aggressive interactions. Calling alone is energetically expensive for frogs, and when combined with locomotion and physical contests, the energy demands are significant.

From Eggs to Adults

Once a female selects a male and enters his territory, mating proceeds through inguinal amplexus. The male grasps the female from behind, just behind her forelimbs, and rides on her back. His enlarged, muscular forelimbs—a sexually dimorphic trait—allow him to maintain this grip for extended periods in the competitive breeding environment.

The female chooses a shallow, vegetated site and lays a massive batch of up to 20,000 eggs, while the male simultaneously releases sperm for external fertilization. The eggs form a thin, floating sheet that can cover an area of 5 to 11 square feet on the water surface.

Temperature is critical for embryo development. The optimal range is between 75-86°F (24-30°C), and under these conditions, eggs hatch in just three to five days. If water temperatures rise above 90°F (32°C), developmental abnormalities occur, and if it drops below 59°F (15°C), normal development completely stops.

Newly hatched tadpoles are fascinating creatures in their own right. They initially have three pairs of external gills and several rows of labial teeth. They show a preference for shallow water with fine gravel bottoms and structural complexity—probably because these areas offer better protection from predators. As they grow, they gradually move into deeper water.

Bullfrog tadpoles feed by pumping water through their gills using rhythmic movements of their mouth floor. This water passes through a filtration organ in their pharynx where mucus traps bacteria, single-celled algae, protozoans, pollen grains, and other tiny particles. As they mature and grow larger, they begin ingesting bigger particles and using their teeth for rasping plant material. You can recognize bullfrog tadpoles by their downward-facing mouths, deep bodies, and tails with broad dorsal and ventral fins.

The time to metamorphosis varies dramatically based on geography and climate. In the warm southern parts of their range, tadpoles can transform into frogs in just a few months. In northern populations where cold water slows development, the tadpole stage can last up to three years. This extended larval period is one of the longest among North American frogs.

In the wild, bullfrogs typically live 8 to 10 years, though one captive individual survived for almost 16 years. Throughout their lives, they continue to grow, with larger individuals generally being older and more experienced.

Who Eats Bullfrogs?

Despite their size and defensive capabilities, bullfrogs serve as important prey for many animals. Their predators span an impressive size range—from 150-gram belted kingfishers to 1,100-pound American alligators. Large herons are particularly adept bullfrog hunters, as are North American river otters and various predatory fish.

The eggs and tadpoles are unpalatable to many salamanders and fish due to chemical defenses. However, their high activity levels can make them more noticeable to predators not deterred by their unpleasant taste. The tadpoles’ constant movement and feeding activity, while necessary for growth, also increases their visibility to potential predators.

Adult bullfrogs have several defense strategies. Their first response to danger is typically to splash and leap into deep water where they’re harder to catch. If cornered or grabbed, a bullfrog may emit a piercing scream that can startle an attacker enough to allow escape. This alarm call also serves to warn other nearby bullfrogs of danger, causing all of them to retreat to safety.

Interestingly, bullfrogs show at least partial resistance to the venom of copperhead and cottonmouth snakes. These venomous snakes are known natural predators of bullfrogs, along with northern water snakes, but bullfrogs have evolved some degree of protection against their toxins. This resistance, combined with their resistance to other defensive chemicals (like wasp stingers and stickleback spines), helps explain their success as predators of well-defended prey.

The Bullfrog’s Competitive Edge

What makes bullfrogs such successful invaders in non-native habitats? Several traits work together to give them a serious competitive advantage.

First, their generalist diet allows them to exploit food resources across different environments. Stomach content studies reveal that adult bullfrogs regularly consume predators of their own young—including dragonfly nymphs, garter snakes, and giant water bugs. By eating the animals that would normally control their juvenile populations, bullfrogs essentially remove the ecological checks on their own population growth.

Second, they seem remarkably resistant to the antipredator defenses of other organisms. Studies of bullfrog populations in New Mexico show regular consumption of wasps with no learned avoidance despite the painful stings. Along the Colorado River, stomach contents reveal they happily eat stickleback fish despite their uncomfortable spines. There are even reports of bullfrogs consuming scorpions and rattlesnakes.

Third, research suggests bullfrogs are capable of niche shifting. Analysis of bullfrog populations at various sites in Mexico, compared with endemic frog species, shows bullfrogs can adjust their ecological role to exploit available resources. This flexibility means they could potentially threaten Mexican frog species that aren’t even currently in direct competition with them.

Scientific and Educational Value

Beyond their ecological impact, bullfrogs have contributed significantly to scientific knowledge. They’re commonly used for dissection in biology classes, helping countless students learn about vertebrate anatomy. The bullfrog genome—weighing in at approximately 5.8 billion base pairs—was published in 2017 and now serves as an important resource for amphibian research, particularly for the Ranidae family.

The species name “catesbeianus” honors Mark Catesby, an English naturalist who documented American wildlife in the 18th century. Some authorities use the scientific name Lithobates catesbeianus, while others prefer Rana catesbeianus, reflecting ongoing taxonomic discussions about the classification of North American ranid frogs.

Albino bullfrogs are occasionally kept as pets due to their striking appearance, and bullfrog tadpoles are often sold at pond supply stores or fish markets. However, prospective pet owners should be aware of the longevity (potentially 16 years in captivity), size, and specialized care requirements these amphibians demand.

Human Interactions

Throughout their range, bullfrogs have a long history of human use. Frog legs are considered a delicacy, especially in the southern United States where bullfrogs are plentiful. This culinary value has been the primary driver behind the bullfrog’s worldwide distribution—humans introduced them to new regions specifically for farming and food production.

Commercial frog farming operations exist in many countries, though escaped or released individuals from these facilities have contributed significantly to the establishment of invasive populations. The combination of high fecundity (20,000 eggs per clutch), adaptability, and skittishness makes escaped bullfrogs particularly difficult to recapture once they’ve entered wild habitats.

The bullfrog represents a fascinating case study in the unintended consequences of species introductions. What began as efforts to provide food sources or control other pest species has resulted in a globally invasive amphibian that’s disrupting ecosystems on multiple continents. Yet in their native range, these same characteristics—voracious appetite, high reproductive output, adaptability—make bullfrogs successful and ecologically important components of wetland communities.

Whether you encounter them as the bass voices of summer night choruses, impressive predators at the pond’s edge, or cautionary examples of invasive species impacts, American bullfrogs remain one of North America’s most remarkable and recognizable amphibians.

Sources: